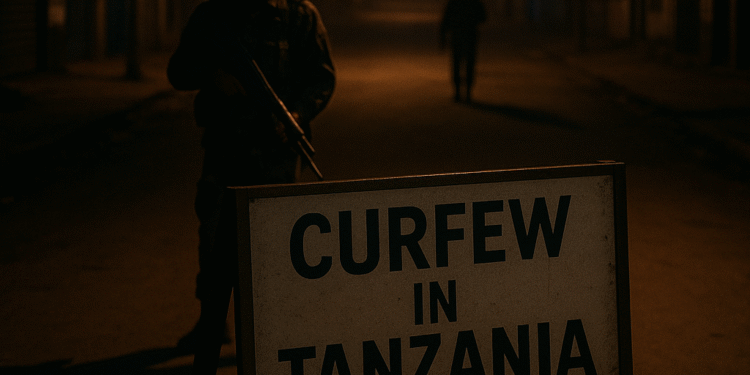

Tanzanian police have lifted a night-time curfew in the capital, Dar es Salaam, a week after it was imposed during deadly post-election protests, as the city shows tentative signs of returning to normal.

The move comes after a period of intense turmoil that saw a nationwide internet blackout, shuttered businesses, and the closure of schools and public transport. While traffic has resumed and some shops have reopened, long queues at petrol stations and a still-restricted internet connection reveal a nation still recovering.

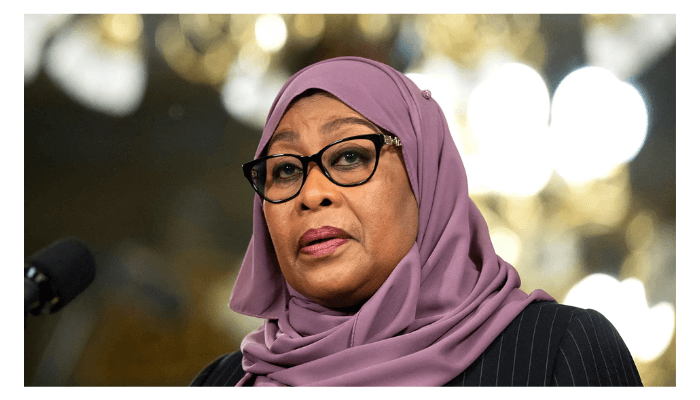

The unrest followed an election that international observers from the Southern African Development Community (SADC) stated “fell short of democratic standards”. The vote, which handed President Samia Suluhu Hassan a second term with 98% support, was conducted with the two main opposition leaders barred from participating—one imprisoned on treason charges and the other disqualified on technicalities.

Beneath the surface of the easing restrictions, a profound human rights crisis festers. The opposition Chadema party claims “no less than 800” people have been killed, while a diplomatic source cited credible evidence of at least 500 deaths. The UN has reports of at least 10 fatalities.

A doctor at Dar es Salaam’s Muhimbili Hospital reported that vehicles marked “Municipal Burial Services” have been collecting bodies from the mortuary at night, taking them to unknown destinations and preventing families from claiming their relatives. “Relatives are not being given the bodies,” the doctor stated.

Despite the scale of the violence, the government has downplayed the casualties and, during her inauguration, President Samia suggested it was “not surprising” that some of those arrested were foreign nationals.

Why It Matters

The lifting of the curfew is not a resolution, but a tactical de-escalation by a government desperate to project control and normalcy after a brutal crackdown. This “calm” is fragile and superficial, achieved through the silencing of dissent—both by force and by a digital blackout. While the streets may be quieter, the fundamental crisis of legitimacy remains unaddressed.

An election with jailed opponents and a 98% result is not a democratic process; it is a coronation. The international community’s tepid concern is inadequate for the scale of this atrocity. True peace cannot come from simply ending a curfew, but from accountability for the lives lost and the restoration of a genuine political space.