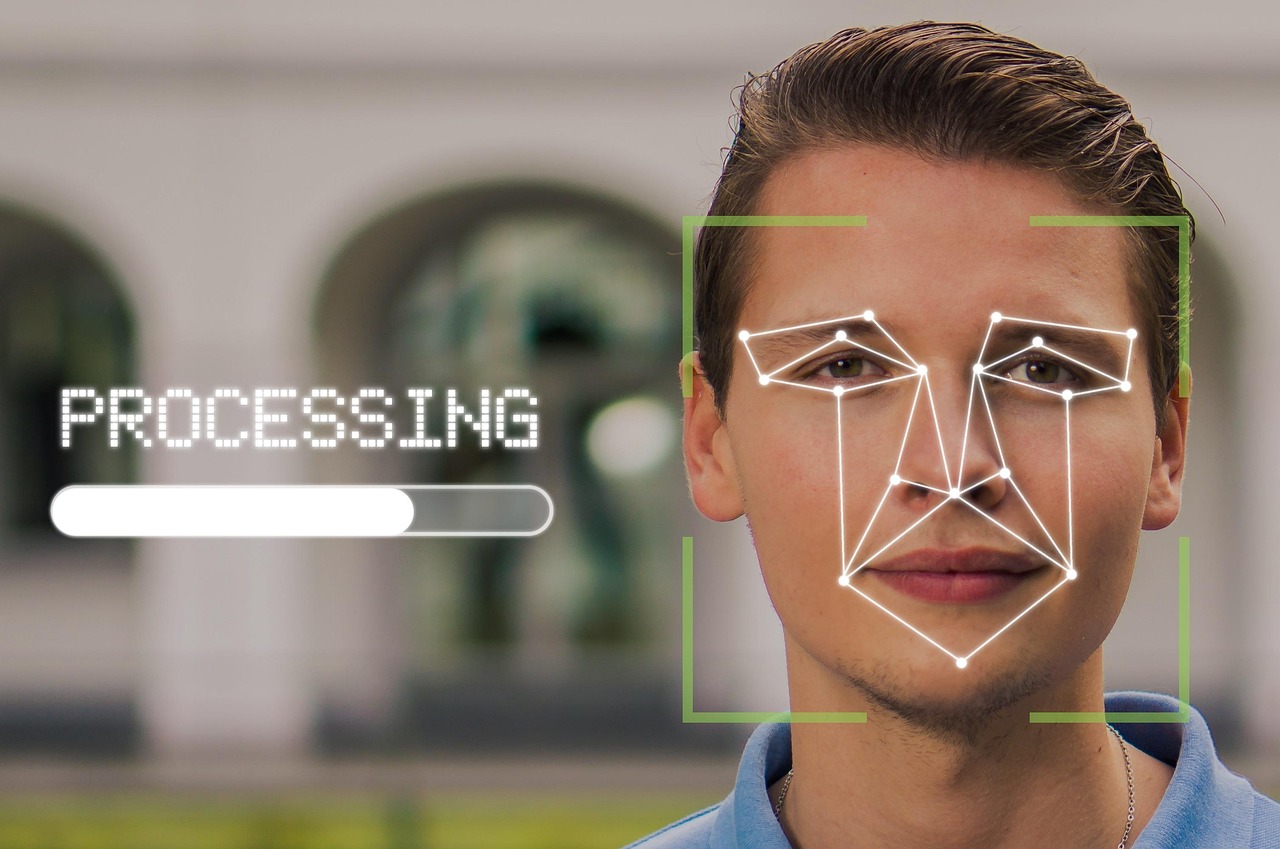

India’s Unified Payments Interface (UPI) is set to revolutionize payments yet again. Starting October 8th, users will have the option to authenticate transactions using facial recognition and fingerprints, a major shift from the long-standing numeric PIN system.

This is an acceptance of biometric payment authentication that will fundamentally reshape the user experience and is poised to boost financial inclusion for millions. The verification process leverages biometric data already stored under the Government of India’s unique identification system, Aadhaar, following recent Reserve Bank of India (RBI) guidelines.

While the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) showcases this at the Global Fintech Festival, it’s important to move beyond simple reporting and critically analyze the profound trade-offs inherent in this massive integration of sensitive personal data. This move is undoubtedly a leap for convenience as it eliminates the friction of remembering and entering a PIN for every transaction makes digital payments more seamless and intuitive, especially for senior citizens and new-to-digital users.

Furthermore, biometric authentication offers a more robust defence against PIN-related fraud, which the RBI has been keen to mitigate. A unique physical trait is, in principle, much harder to steal or ‘shoulder-surf’ than a simple four or six-digit number. UPI’s success has always been its ability to be accessible to all, and this feature, particularly the Aadhaar-based face authentication for setting up a UPI PIN without a debit card, makes onboarding faster and dramatically more inclusive.

Why It Matters

The very aspects that make this technology so compelling are the sources of its greatest risk: centralization and the immutability of biometric data. The architecture connects a high-frequency payment system like UPI to the vast, central biometric reservoir of Aadhaar.

This aggregation of unique, permanent identifiers creates a “honey pot” that magnifies the consequences of any potential cyberattack or insider breach. Unlike a PIN, a compromised fingerprint or facial map cannot be changed. The damage, if a breach occurs, is a permanent and deeply personal identity theft that lasts a lifetime.

The government must aggressively address the privacy and data protection concerns. Biometric data is not just a digital key; it’s also an intimate marker of a person. The potential for its misuse (whether for mass surveillance, intrusive profiling, or discriminatory practices by private entities) is a profound ethical dilemma that a democratic society cannot afford to ignore. The current regulatory environment, specifically the Digital Personal Data Protection Act of 2023, is still pending final rules, creating a concerning vacuum where innovation is outpacing adequate legal guardrails.