Every December, Nollywood steps into its most important season. This is the month filmmakers pray for all year. Families are on holiday. Young people want to unwind. Cinemas are packed. Tickets are more expensive. In theory, everyone should win. But year after year, the same ugly fight returns. Filmmakers complain. Audiences complain. And cinemas stay quiet.

This December is louder than usual. Several respected filmmakers have come out to say what many have whispered for years: some cinemas are deliberately frustrating certain films. Not because the films are bad. Not because audiences are uninterested. But because the system itself has chosen favourites.

And once again, only one name seems untouchable.

The Exception That Proves the Problem

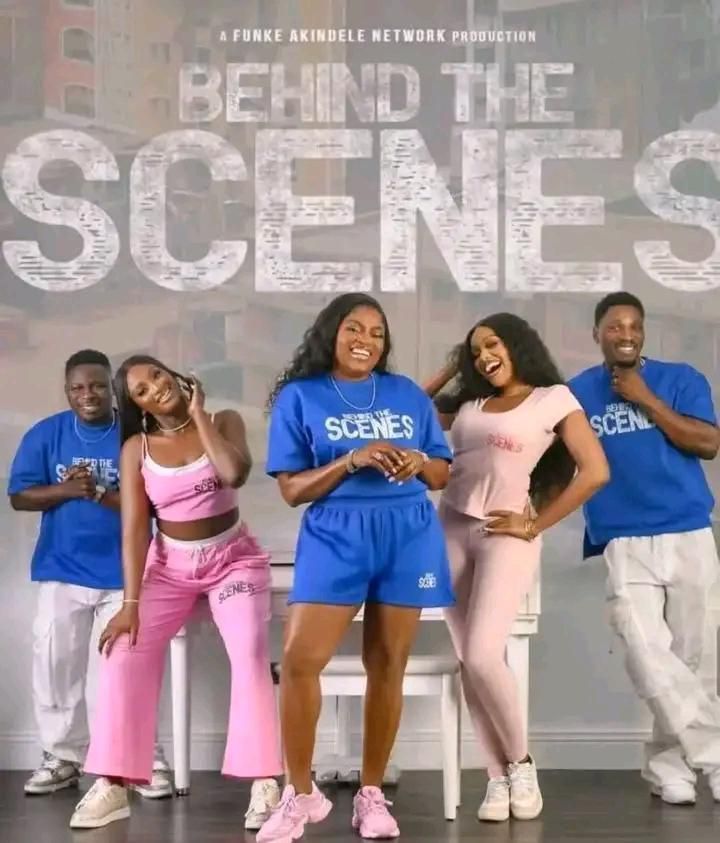

In the middle of all this chaos sits Funke Akindele. Her film has grossed over ₦500 million in barely three weeks. Full screens, prime time slots, multiple daily showings. No stories of missing screenings or confused audiences. No public fights. No petitions.

This is not to attack her. Funke Akindele has earned her place through years of consistency, audience trust, and box-office discipline. She understands the game better than most. But her success forces us to ask a hard question: if one filmmaker can dominate the same cinema system without issues, why are others constantly blocked?

Is this really about quality? Or is it about power, relationships, and control?

What Filmmakers Are Actually Complaining About

Toyin Abraham says her film Oversabi Aunty is being pushed into dead time slots. 10 am. 9 pm. Times when working people are unavailable, and families are still asleep or already heading home. She says some cinemas sell tickets under false pretences, then redirect audiences into her hall without honesty. That is not business, that is deception.

Niyi Akinmolayan goes further. He alleges that tickets were sold for Colours of Fire and audiences showed up, only to be told the film would not be screened.

Ini Edo, producing her first film, shared videos of confused moviegoers and spoke openly about emotional exhaustion. Her words matter because first-time producers are the most vulnerable. If this is how newcomers are treated, what message are we sending to the next generation of filmmakers?

How Cinema Money Really Works

When a film enters cinemas, the money does not go straight to the filmmaker. First, cinemas take their cut. Distributors take another cut. Marketing costs are deducted. Only after weeks, sometimes months, does the producer see returns.

This means one thing: screen time is everything.

If a film gets only one showing per day while another gets five, the outcome is already decided. If a film is placed at unfavourable hours, its “poor performance” becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Then the same cinemas point to low numbers as justification to remove the film entirely.

It is a quiet, efficient way to kill a movie without ever saying its name.

December as a Weapon

Cinemas know this is the only window many filmmakers have to recover investments. They know pressure is high. They know filmmakers cannot easily pull out. So control becomes a weapon. Screen allocation becomes a punishment or a reward. And once a few dominant titles are protected, everyone else becomes collateral damage.

This is why the same complaints resurface every December. Not March. Not July. December.

Because this is when power matters most.

Are Filmmakers Even Making Enough Money?

Here is the painful truth: many are not.

After months or years of production, loans, personal savings, and emotional sacrifice, some filmmakers leave cinemas barely breaking even. Others lose money entirely. Yet the headlines still say “sold out” and “box office success.”

Sold out for whom?

If audiences are misinformed, if screenings are cancelled, if showtimes are manipulated, then the box office numbers no longer reflect audience choice. They reflect gatekeeping.

And investors are watching.

Who Is Watching the Cinemas?

This is where the conversation gets uncomfortable, and where it must be honest. Today, Nigerian cinemas operate in a space that is largely unmonitored when it comes to business conduct. While the National Film and Video Censors Board (NFVCB) licenses films and cinema premises for exhibition, it does not actively regulate how films are screened, how many times they are shown, how tickets are sold, or whether a film advertised is actually the film being shown. In other words, content is regulated, but conduct is not. And in that gap, abuse thrives.

The Cinema Exhibitors Association of Nigeria (CEAN), often mentioned in these conversations, is not a regulator. It is a trade association — a body formed by cinema owners to represent their interests. CEAN has no legal authority to sanction cinemas, no statutory power to enforce transparency, and no obligation to protect filmmakers. Expecting CEAN to discipline cinemas accused of unfair practices is like asking a club to punish itself. It is structurally conflicted. It was never designed to protect producers, investors, or audiences.

At this point, Nigeria does not just need guidelines. It needs a dedicated, independent cinema regulatory framework. A body empowered to monitor exhibition practices, enforce transparency in ticket sales, penalise deliberate misinformation, and protect the economic interests of filmmakers and investors. An industry this large cannot be left to self-policing, especially when billions of naira and hundreds of jobs are at stake.

The pies Nollywood should be baking now must be large enough for everyone to eat. Not hoarded. Not rationed. Not weaponised.