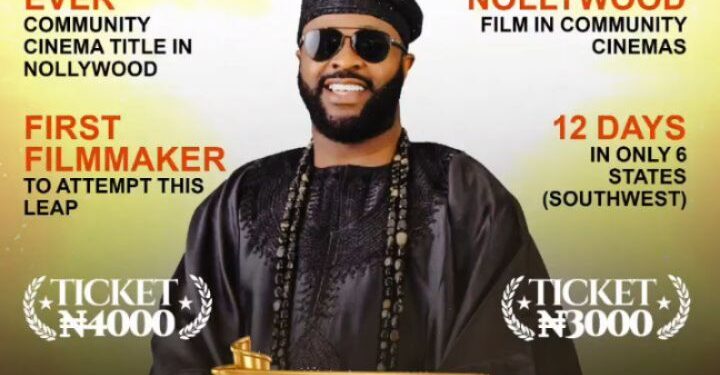

Before anyone celebrates or dismisses this moment, the first question must be asked plainly: is Femi Adebayo telling the truth?

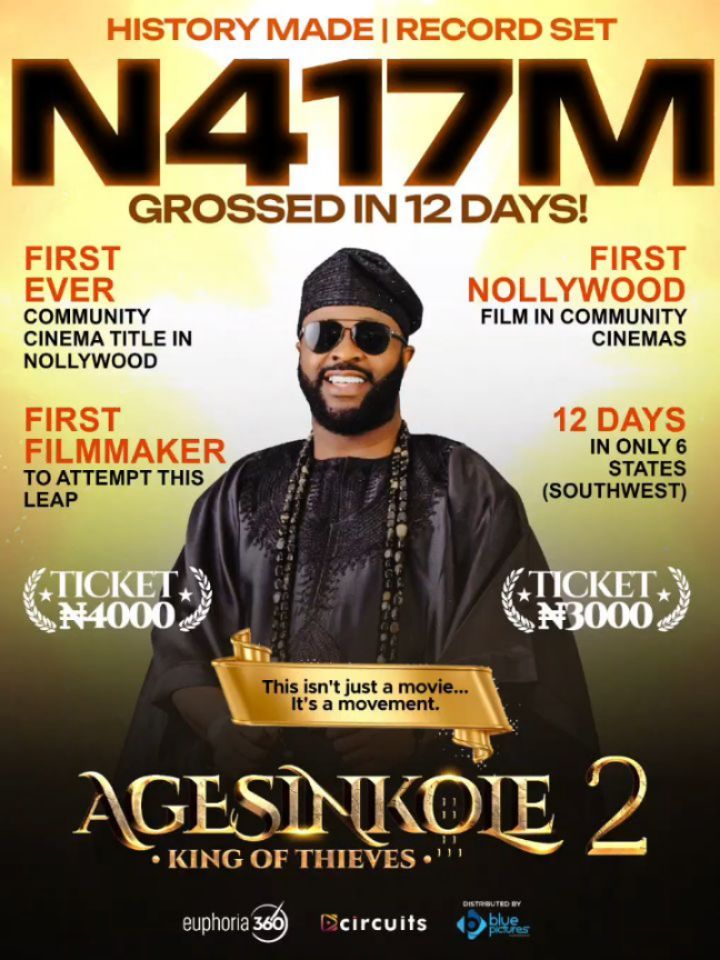

₦417 million in 12 days, outside the traditional cinema system, sounds almost unbelievable in an industry where even major multiplex releases struggle with transparency.

Let Us First Ask the Hard Question: Is ₦417 Million Possible?

Nigeria is a country of over 220 million people, yes, but cinema attendance is not evenly spread. Most Nollywood box office revenue traditionally comes from Lagos, Abuja, and a few urban centres. Even then, only about 102 cinemas serve the entire country, reaching roughly 2.79 million people annually.

So how does a film, not showing in all states, not using major multiplexes, generate ₦417 million in 12 days?

Let us break it down without emotion.

Tickets were reportedly sold at ₦4,000 in Lagos and ₦3,000 elsewhere. Even if we average this to around ₦3,500, that means roughly 119,000 tickets were sold in less than two weeks.

Spread across multiple locations, across peak festive days, across states with strong Yoruba cultural ties to the film, the number is not impossible. Difficult, yes. Unprecedented, yes. But mathematically impossible? No.

The real issue is not whether the number can exist. The issue is verification and transparency.

So, Is Femi Adebayo Lying? Or Is He Doing Something New?

There is currently no evidence that Femi Adebayo fabricated the figure. The project involved established distributors, Euphoria 360, Circuits, and Blue Pictures, not unknown entities. The screenings were not private house parties; they were paid-entry events across multiple towns and cities.

However, unlike traditional cinemas where ticket sales are logged digitally and audited through central systems, community cinemas operate differently. Sales are more fragmented. Reporting is less standardized. That is where skepticism comes from, and rightly so.

This does not automatically mean deceit. It means the industry lacks a unified measurement system for alternative exhibition models. The discomfort many feel is less about Femi Adebayo and more about the structure in that space

Community Cinemas: Less Politics, Less Gatekeeping

One of the quiet but powerful implications of this model is how it reduces cinema politics.

Traditional cinemas are few. Just over 100 cinemas serve a country of more than 200 million people. That imbalance has created power concentration. Whoever controls screens controls narratives, release dates, showtimes, and revenue flow.

Community cinemas disrupt that monopoly.

There are fewer politics because:

- There is no battle for prime slots

- There are no artificial “sold out” claims

- There is no quiet sidelining of films

- There is no forced competition under the same roof

Instead, filmmakers deal more directly with exhibitors and audiences. The relationship becomes simpler and more transparent.

But Does Less Politics Mean Less Money?

This is the big fear. Community cinemas mean cheaper tickets. Cheaper tickets suggest lower revenue per seat. But that logic only works if volume remains the same.

What Femi Adebayo proved is that volume increases when access increases.

People who never step into a multiplex showed up. Families attended together. Viewers who would wait for streaming to pay to watch immediately. The audience base expanded instead of recycling the same urban crowd.

Lower margins per ticket were offset by sheer numbers.

Is This the End of Distribution Houses?

This model will not kill distribution companies at least not immediately. Big-budget films, nationwide releases, and premium experiences still need structured cinema chains.

What community cinemas do is break monopoly thinking. They tell distributors: you are no longer the only path to the audience. That is healthy pressure.

In fact, smart distributors will adapt. They will hybridize. Combine traditional cinemas with community rollouts. Use community screenings to build momentum before premium releases or streaming deals.

If they do not adapt, they will become irrelevant.

Government Policy Quietly Made This Possible

This experiment did not happen in a vacuum. In 2024, the Nigerian government waived licensing fees for community cinema investors. The National Film and Video Censors Board (NFVCB) approved a 12-month pilot for community cinema projects.

That policy shift matters. It lowers entry barriers. It encourages infrastructure growth. It signals official recognition that Nigeria’s cinema ecosystem cannot survive on malls alone.

When the Executive Director of NFVCB described community cinemas as a “low-hanging fruit,” it was not poetic language; it was economic reality.

Infrastructure Is the Real Story Here

Industry voices like Joy Odiete of Blue Pictures have been saying this for years: exhibition is Nollywood’s biggest bottleneck. Production has grown, talent has grown. Audiences exist. But screens are too few. Community cinemas are not a downgrade. They are an expansion layer.

School halls, refurbished town cinemas, open-air venues, mobile screens, these are not compromises. They are solutions tailored to Nigerian reality.

This experiment exposes a truth many stakeholders are uncomfortable with: Nollywood does not actually lack audiences. It lacks access.

When filmmakers bypass traditional choke points and still succeed, it forces everyone to rethink who really holds power. That is why this model feels disruptive.

It suggests that filmmakers can negotiate differently, release differently, and still win.

Giving Femi Adebayo His Flowers

Whether the final audited figure ends at ₦417 million or lower, one thing is clear: Femi Adebayo thought differently. He took a risk. He stepped outside a system many complain about but few challenge structurally.

That courage deserves respect.

Nollywood cannot grow by repeating the same model every December and expecting different results. Innovation will look uncomfortable before it looks successful.

What This Means for Nollywood’s Future

Community cinemas are not a silver bullet. They require regulation, safety standards, reporting systems, and trust. But they also represent scale, something Nollywood desperately needs.

If Nigeria has over 200 million people, why should only a few million ever experience films on a big screen? What Agesinkole 2 has done is remind Nollywood of something basic: cinema is not a building, it is an experience.

When that experience is accessible, people show up. When it is distant, expensive, or politicized, they disappear. Femi Adebayo’s experiment is not just a success story. It is a question thrown at the industry: What if the future of Nollywood is not bigger malls, but more doors?

And for the first time in a long time, that question feels dangerous in the best possible way.