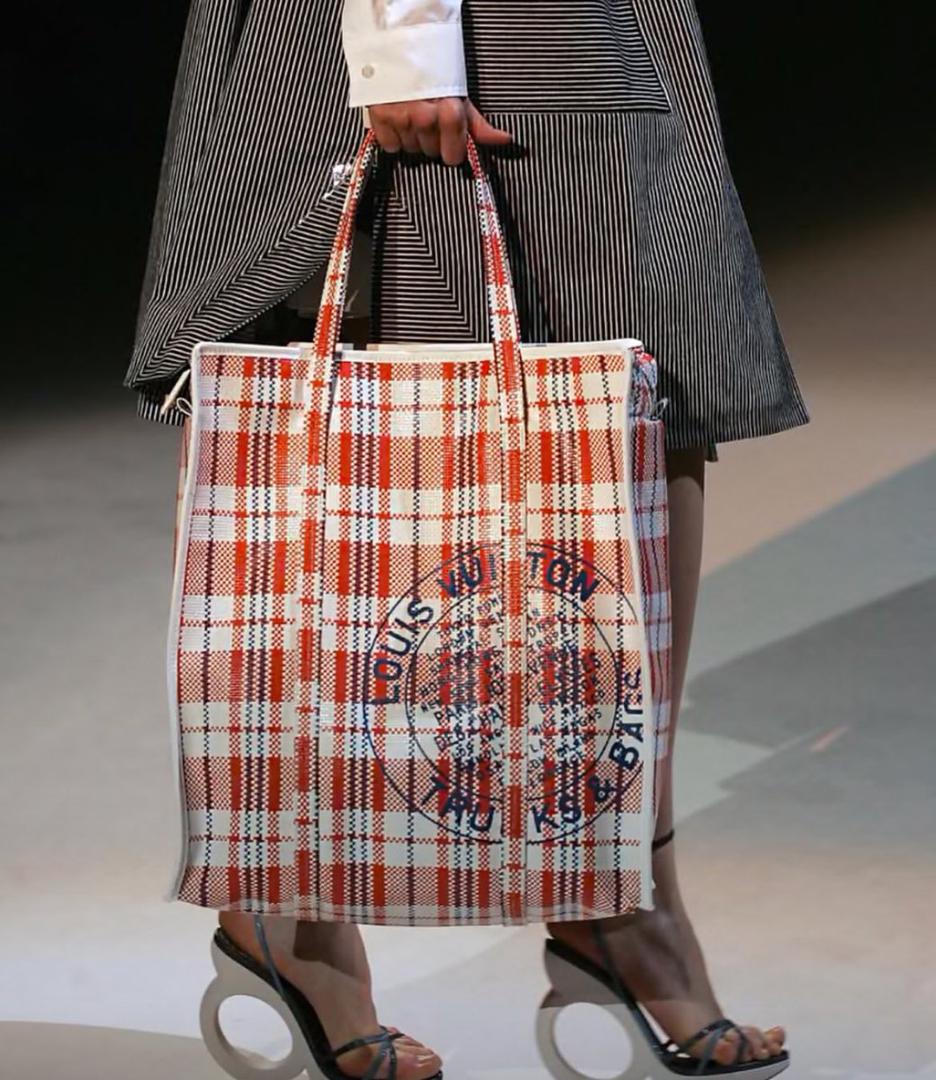

The simple but iconic checkered weave of the “Ghana Must Go” bag is not a new trend waiting to be discovered by a luxury atelier; it has a deep cultural meaning. It is a durable, practical luggage used for centuries by traders and travelers, which was unfortunately baptized with a name of national cruelty, a.k.a the 1983 mass expulsion of over a million Ghanaians and other West Africans from Nigeria. So it comes as no surprise that this bag holds the physical and emotional weight of displacement, fear, and shattered livelihoods.

Therefore, when a big name fashion brand like Louis Vuitton whose very core is synonymous with untouchable, exclusionary luxury uses this pattern and merely stamps it’s logo on it, the result is nothing short of a fashion crime. Fans may argue that this is “inspiration” but it is infact, not. It is however, a lazy and callous act of cultural theft. Luxury’s gaze, in this instance, functions as a predatory filter, stripping the object of its socio-political meaning and its history of trauma, and re-dressing it for the consumption of the mostly western elite.

In summary, this is a profane fetishization of poverty and pain, and by transforming a symbol of a refugee’s necessity into an expensive, ironic accessory, Louis Vuitton has shown a deliberate disregard for their ‘inspiration’s’ material’s deep-seated significance. The brand is essentially selling the story of a chaotic, forced exodus, of West African trauma, for a profit, all while neglecting to acknowledge or compensate the people whose lives gave the design its power.

On Reclaiming the Narrative

The critique of cultural appropriation in fashion must shift from mere outrage to a demand for structural change. The responsibility rests not only with the designers, but with the entire luxury ecosystem (from the brand executives to the consumers). Any luxury brand that has, or will, profit from the “Ghana Must Go” pattern must be compelled to dedicate a substantial, ongoing percentage of the revenue from that line (and perhaps all future ‘culturally inspired’ lines) directly to West African migrant and refugee aid organizations.

True inspiration is collaborative, not extractive and instead of appropriating a pattern, Louis Vuitton and its peers should be initiating equitable, long-term creative directorships and partnerships with West African designers and artisans. Imagine the power of a collection where a brilliant Ghanaian or Nigerian creative is given the global platform and resources to interpret the checkered weave with their own narrative of resilience and beauty.

The Louis Vuitton model however, shifts the dynamic from one of theft to one of power-sharing and wealth distribution, proving that ethical fashion should and must exist. Finally, the luxury consumer holds the power to end this cycle. The price of this bag isn’t for the mere mortal (a.k.a average person). Consumers must stop buying stories of suffering dressed up as haute couture. The fashion world must recognize that heritage is is the soul of a people and not simply a trend board. It is also not for sale at any price, especially not one that only lines the pockets of a distant, indifferent few.