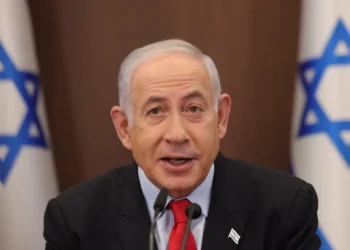

The luxury buses lined up after dark, company logos gleaming under floodlights: Zenco, OHAMs Divine, C-Energy. Make no mistake here; it was a political declaration and a high-stakes gamble by some of the Southeast’s most prominent businessmen that the path to relevance runs not through opposition, but through proximity to power.

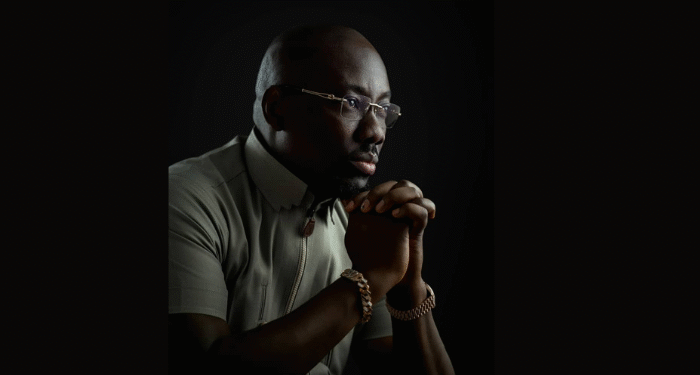

Obi Cubana, Cubana Chief Priest, Zenco Oil CEO Cletus Uzoezie Oragwa, and C-Energy boss Christian Okonkwo have donated a fleet of air-conditioned luxury buses, worth several hundred million naira, to the City Boy Movement—a Tinubu-aligned youth mobilization platform run by the president’s son, Seyi Tinubu. The vehicles will be branded with campaign messages and deployed across all five Southeastern states ahead of the 2027 election.

But the buses carry more than passengers. They carry a question that neither the donors nor their critics can answer: What, exactly, are they buying?

“We Can’t Afford to Lose Again“

The men behind the donation have been blunt about their strategic pivot. Cubana Chief Priest, who openly admits he worked for Peter Obi in 2023, posted his new credo to millions of followers:

“Our minds are made up. The goal is simple: deliver @officialasiwajubat. We won’t be on the bench again for another four years. As smart stakers, we are banking on Asiwaju this time. We can’t afford to lose again.”

Read that language carefully. Not “we believe.” Not “we support.” But “We are banking on.” This signifies investment. These men are placing a bet, and they expect (massive) returns.

Obi Cubana, appointed Southeast Coordinator of the City Boy Movement in a choreographed handover ceremony with Seyi Tinubu, offered his own rationale: “The South East can never be sidelined anymore because we are now fully involved. Very soon, our people will begin to feel the impact.”

The implication is unmistakable. Sidelining stops when involvement begins. And involvement, in this formulation, means alignment with the party in power.

The Silence at the Center of the Room

But here’s what the donors have not said.

They haven’t cited the ₦2.5 trillion in federal road contracts allocated to the Southwest versus the ₦446 billion—barely 18%—earmarked for the Southeast under Tinubu.

They haven’t mentioned that while Ogun State alone boasts five full cabinet-rank ministers, the Southeast’s five ministers include three junior portfolios.

They haven’t referenced Ohanaeze Ndigbo’s repeated protests over the “glaring exclusion” of Igbo professionals from federal boards and parastatals, nor the fact that the Southeast got zero representation on the Presidential Committee for the 2025 National Population Census.

They haven’t demanded redress for a region that, according to former lawmaker Linus Okorie, has been “systematically sidelined” in infrastructure allocation, appointments, and access to the president’s inner circle.

They haven’t said any of this. Instead, they’ve declared that the solution to marginalization is not to protest or stage opposition but rather proximity. The silence of these billionaires is the strategy.

Very Dark Man’s Criticism

The backlash has been ferocious, particularly from the Obidient movement that once regarded these men as financial pillars of Peter Obi’s 2023 campaign. A coordinator of the movement in the FCT, speaking anonymously, didn’t hide his shock: “He was among the major financial chiefs behind Obi. Obi’s air travels were mainly financed by that wonderful Igbo son. We did not see this coming.”

Influencer VeryDarkMan delivered the most scathing indictment: “Your tribesman is contesting for president and happens to be the most qualified candidate, yet you left him because of money. Igbo can never be president of this country because they are always fighting one another.”

The accusation—ethnic betrayal for personal enrichment—has trailed Cubana across social media. His defenders counter that politics is about interest alignment, not sentiment. One netizen wrote: “South East have alienated itself for too long. You can only get what you want for your region through alignment and negotiation.”

This is precisely the argument the donors are making, without quite saying it aloud.

What “Involvement” Actually Buys

Political activist Deji Adeyanju offered a cold-eyed assessment: “Obi Cubana is from Anambra, the same state as Peter Obi, and the governor of that state is already working for Tinubu. Most Labour Party lawmakers elected in the state have defected to the APC. Is it a businessman who should be fighting Tinubu when governors and legislators have moved on?”

The calculus is brutally simple. If the entire political class of the Southeast is aligning with the presidency, isolation becomes existential risk. The buses therefore become an insurance premium.

“The South East Can Never Be Sidelined Anymore”

The phrase above is Obi Cubana’s, and it contains multitudes. “The South East can never be sidelined anymore because we are now fully involved.”

The admission—that the region has been sidelined—hangs in the air, unadorned by demands. Cubana does not say “and therefore we expect X, Y, or Z.” He does not present a list of federal projects, ministerial slots, or board appointments. He simply asserts that involvement is the antidote to exclusion.

Linus Okorie, the former lawmaker, urges Southeast residents to treat voter registration as “a collective redemptive duty,” arguing that “the silence of the people is not consent or cowardice; it is the quiet gathering of strength, the calm before a decisive democratic verdict.”

Ohanaeze Ndigbo insists that “supporting regional development initiatives and insisting on equity at the federal level are not contradictory” and has called on Tinubu to redress the “still-redeemable imbalance” in appointments.

But the billionaires have chosen a different path.

The Bet and Its Payoff

The buses will roll through Anambra, Imo, Enugu, Abia, and Ebonyi in the coming months, branded with messages of continuity and “Renewed Hope.” They will ferry supporters to rallies, transport logistics teams, and serve as mobile billboards for Tinubu’s re-election.

What they won’t carry is any explicit commitment from the presidency about what the Southeast gets in return. That transaction will happen, if it happens at all, in private conversations, unrecorded meetings, and the quiet distribution of influence that characterizes Nigerian political economy.

Cubana Chief Priest insists he has made the smart choice. “To comot Asiwaju is a total impossibility,” he declared. “Who wan do am? How they wan take do am?”

To him, it is the logic of the inevitable and the reasoning of men who have studied Nigerian political history and concluded that opposing the machinery of incumbency is a fool’s errand.

From their point of view, it’s better to be inside the room, even at the cost of silence about the room’s injustices.

What Remains Unspoken

The donors have not, in any public statement, framed their donation as a transaction for federal inclusion. They haven’t said: “We gave buses; we expect roads.” They haven’t explicitly linked their support to the ₦2 trillion disparity in infrastructure allocation or the absence of Igbo voices in Tinubu’s kitchen cabinet.

But they don’t need to. The inference is baked into every word they’ve spoken.

“Time has come for us to be part of the system.”

“The South East can never be sidelined anymore.”

“We won’t be on the bench again.”

These are not the statements of men content with the status quo but rather, the statements of men who have studied the bench, measured its distance from the field, and decided they would rather play than protest.

Whether their gamble pays off—whether the buses translate into asphalt, portfolios, and presidential audience—will determine not only Tinubu’s performance in the Southeast in 2027, but whether the region’s elite continue to believe that silence is the shrewdest investment of all.

For now, the buses are parked, the engines are warm, and the question lingers unanswered.

What seat, exactly, are they buying?