First, let me express my gratitude to both Ahmad Adedimeji Amobi and Lolade Siyonbola for the insight, the questions, and the passion that fuelled their respective pieces. Ahmad asked a question we often whisper amongst ourselves but rarely confront publicly: Where exactly is Nollywood in the world? Lolade’s beautiful and deeply stirring response gave that question both context and heart.

This piece is my humble attempt to join that conversation. To extend it. To say: yes, Nollywood is at a crossroads, but perhaps more than anything, this moment is an opportunity. The chance to look ourselves in the mirror and decide who we are and where we are going.

Nollywood Isn’t Invisible; It’s Just Not Present Where It Matters

Ahmad asked a pressing question: Where is Nollywood on the global map despite being the second-largest film industry by volume? He told a story of browsing in-flight movies between Paris and Doha and barely finding a Nigerian film listed. Nollywood was hidden under “World Movies,” and only accessible after navigating through the “African” category. This image was symbolic, painful, and true. And Lolade answered that question with clarity: until we return to ourselves, to our indigenous languages and cultural roots, Nollywood will keep circling the global margins.

I agree with both. But I believe the issue goes even deeper. It’s not just a language or cultural problem. It’s about what we are building, how we are building it, and whether we truly believe Nollywood can be an industry of the future, not just a nostalgia factory.

The Issue Isn’t Just Quality. It’s Identity

Lolade made a strong case for the role of language, emotional resonance, and storytelling. She said, and rightly so, that many of our scripts are written in English not because that is the best language to tell the story but because we are thinking of “market access.” But the market can sniff when something is inauthentic. The global audience wants to feel us, not our mimicry of them.

But then we must ask a fair question: what is our culture? Nigeria is not a monolith. We have hundreds of ethnic groups, each with its language, history, and worldview. English is our unifying tongue, yes, but it’s not our cultural language. That diversity should not be a problem. In fact, it is our strength.

Look at Bollywood. Even when their stories are shot in London or Dubai, they are still Indian at the core. Their food, their gods, their clothes, and their songs are non-negotiable. The same with Korean dramas. It’s the same thing with Korean dramas. No matter the theme, the culture is always present. From Soju, to Hanbok, to Korean food like Rameyon—even Nigerians now want to try them. That’s cultural storytelling.

If Nollywood must move from mere recognition to presence, it must learn to sell its roots, not just its scripts.

We Already Have the Stories. Let’s Build the Ecosystem

I watched two Bollywood films back-to-back recently. I could not predict the storyline, the themes were layered, and the endings were unpredictable but satisfying. Even the less “classy” ones had direction. In Nigeria, we have stories too. Look at the myths from our boarding schools. Nemsia Studios just released a trailer for Miss Kanyin, echoing the Madam Koi Koi myth. These are original African tales. The kind that can stand beside any folklore-based content from anywhere in the world.

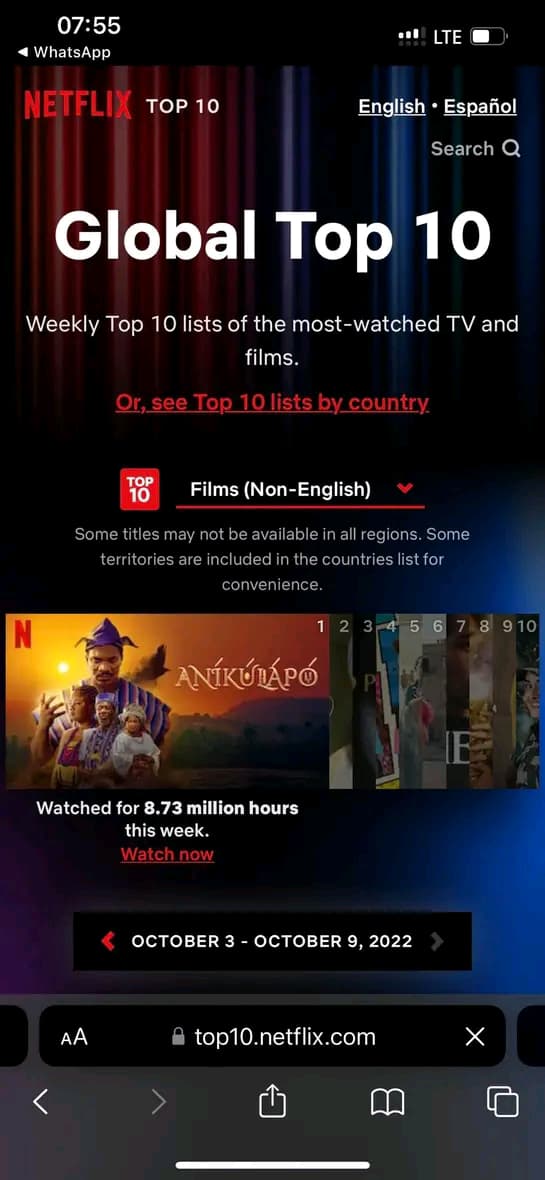

We also have cultural representation. Yoruba filmmakers, for example, have been doing this for a while—Ageshinkole, House of Gaa, Anikulapo, Iyalode, Ayinla, October 1st, Swallow…the list goes on. The issue isn’t whether we are making culturally grounded films. The issue is what we are doing with them. Are we marketing them well? Are we distributing them beyond our borders? Are we packaging them to be understood globally without stripping them of their soul?

The Streaming Pull-Out: A Wake-Up Call, Not the End

Another key point Ahmad raised is the retreat of international streamers like Netflix and Amazon Prime. Ahmad said:

“Just a few years after the excitement of these launches, the consequences of relying on these foreign platforms have begun to surface.”

And he’s right. Amazon has suspended Nollywood funding. Netflix has reportedly slowed down on commissioning Nigerian originals. It’s a cold slap of reality.

But this is also an opportunity.

As filmmaker Blessing Uzzi rightly said:

“No industry survives just on making films and selling them to streamers.”

She’s right. It’s time to go back to the drawing board. We must ask ourselves what we want to be. Do we want to keep begging for Western platforms to take our films? Or do we build our own platforms? With our own rules?

Nollywood’s Global Visibility Must Be Engineered

Global appeal is not accidental. We need our films to appear in-flight menus, hotel TVs, international platforms, and major festival circuits. This means building relationships with curators, critics, film academics, and distributors abroad. It means writing scripts that are both personal and universal.

Mimidoo Bartel said in Ahmad’s interview: “We can’t just restrict ourselves. Coming to places like Series Mania is about meeting distributors, exploring new platforms, and expanding our reach.” She is right. The world won’t come to us unless we show up prepared.

And we must also confront how tech and distribution algorithms can restrict access. As Lolade highlighted, carceral mobility isn’t just about passports, it’s also about data, digital gatekeeping, and racial bias in global media infrastructure.

The Ball Is in Our Court Now

No matter how we say it, the ball lies in the court of those directly involved in the industry. This article is definitely not an answer—I can’t even proffer a solution. All we can do for now is talk, write, and hope someone who can build something concrete is listening.

This is the work. And if we commit to it, there’s no reason Nollywood can’t have its own seat at the global table.