South Africa’s once-dominant African National Congress (ANC) is scrambling to form a unity government after losing its majority for the first time since the end of apartheid. The ANC, which has ruled the nation since Nelson Mandela’s historic 1994 victory, now faces the humbling task of inviting other parties to join it in governance.

The recent elections on May 29 sent a clear message from voters: years of economic mismanagement, unemployment, and rampant corruption won’t be tolerated any longer. President Cyril Ramaphosa, in a bid to salvage the situation, announced that the ANC is open to broad collaborations to steer the country forward.

The opposition parties, while open to discussions, are treading cautiously. The Democratic Alliance (DA), South Africa’s largest opposition party, stated it’s “committed to the process,” but raised concerns about the inclusivity of the ANC’s invitation. DA spokesperson Werner Horn emphasized the need for partners committed to constitutional principles, rule of law, and a social-market economy.

“But the broad invitation to all parties … rather than limiting it to parties committed to our current constitutional dispensation, the rule of law and a social-market economy, has undoubtedly complicated matters,” spokesperson Werner Horn said.

ANC’s Waning Grip

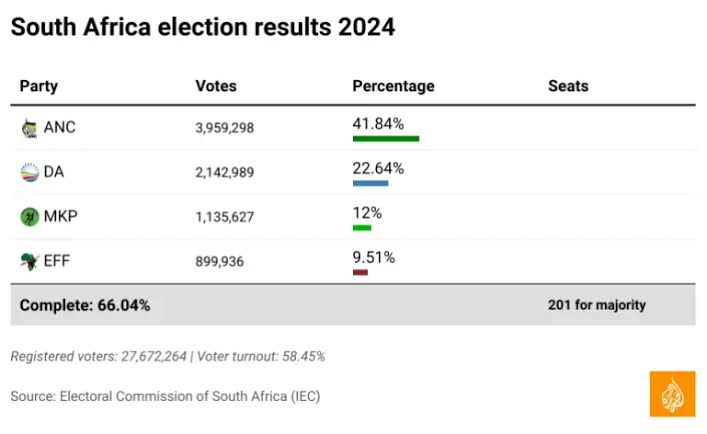

The ANC still holds the largest number of seats—159 out of 400—in the National Assembly. But without a clear majority, it must negotiate with other parties to form a government. The DA follows with 87 seats, while the populist uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK), led by former President Jacob Zuma, has 58 seats. The Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), known for their radical policies, hold 39 seats.

Ramaphosa revealed that the ANC has already engaged in discussions with the EFF and DA, as well as smaller parties like the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), the National Freedom Party, and the Patriotic Alliance. Zuma’s MK also expects talks with the ANC soon.

A “Doomsday Coalition”?

During the campaign, the DA warned that an alliance between the ANC and either the EFF or MK could spell disaster for South Africa’s economy. Both EFF and MK have called for drastic measures like nationalizing mines and land expropriation without compensation—policies that are anathema to the DA’s pro-business stance.

Floyd Shivambu, deputy leader of the EFF, made it clear that they won’t join any government that includes the DA, saying, “We are not desperate for positions in government.”

Meanwhile, the socially conservative IFP, which draws support from South Africa’s Zulu community, expressed cautious optimism about the unity government proposal, stressing that the specifics will be crucial.

The Clock Is Ticking

The pressure is on: the new parliament must convene within two weeks of the election results, and one of its first tasks is to elect a president. This constitutional deadline, around June 16, is fast approaching, forcing the ANC and its potential partners to hammer out an agreement swiftly.

All eyes are on the ANC’s next moves. Will it manage to cobble together a coalition that can govern effectively, or will South Africa face even more political turmoil?