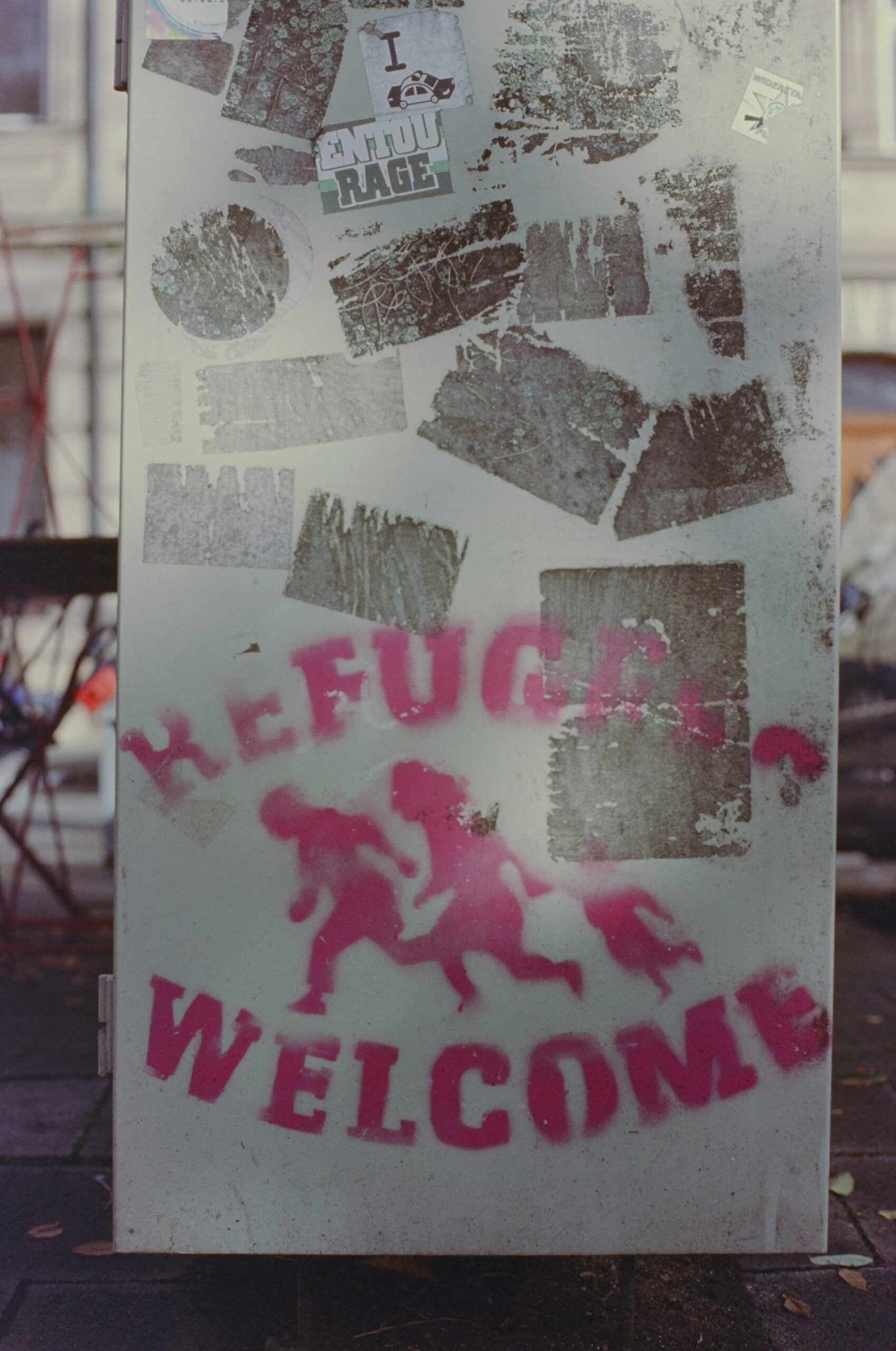

White South Africans are deeply divided over a controversial U.S. offer of refugee status, with families living behind barbed wire and electric gates applying for asylum out of fear of being “slaughtered,” while others reject the narrative of persecution as a dangerous political fiction.

For farmers like Marthinus, who drives through 4-meter-high spiked gates he calls a “prison,” the executive order signed by President Donald Trump is a lifeline. “Our Afrikaner people are an endangered species,” he says, citing murdered relatives and applying for asylum so his family won’t be “hanged on a pole.” This belief in a targeted “white genocide,” promoted by Trump and figures like Elon Musk, has driven thousands to seek refuge.

Yet on the same soil, other white farmers like Morgan Barrett patrol their land nightly due to endemic crime but staunchly reject the racial narrative. “I don’t buy that… the attacks are against whites only,” he states, arguing thieves target wealth, not skin color, and that calling it genocide shows “no real understanding of what a genocide is.” This split is amplified by official data showing that of 18 recent farm murders, 16 victims were Black, underscoring a violence that plagues all races in a nation with one of the world’s highest homicide rates.

Why It Matters

The U.S. asylum offer hasn’t just provided an escape route; it also legitimized a potent, far-right conspiracy theory, validating the deepest fears of some while alienating those who see it as a betrayal of South Africa’s complex reality.

The farmers behind the electric fences are prisoners of a narrative that casts them as a persecuted minority, a view that willfully ignores both the indiscriminate nature of South Africa’s violent crime and the historical context where Black South Africans endured decades of systematic, state-sanctioned persecution under apartheid.

By accepting this asylum framework, the U.S. is not only resourcing refugees; it is actively importing South Africa’s most toxic racial politics, laundering a disputed genocide claim into official American policy. The real division isn’t over safety—everyone agrees crime is rampant—but over identity: whether to see oneself as a besieged tribesman needing rescue, or as a South African facing a shared national crisis that requires a shared solution.